In the early part of 2020, Rev. Dr. James Kelsey traveled from New York state, from a season of “not being reactive“.to Rwanda to understand healing. The journey had a tremendous impact on his life as a husband, parent, minister of God’s Word, regional leader and friend. He encountered the faces of forgiveness and healing. He saw his heart. Here are his reflections:

“What is stunning about Rwanda is not the tragedy of genocide but the healing and wholeness that is being sown in the aftermath of tragedy. Healing is the real story in Rwanda. Perpetrators and victims personally connected to one another through this tragedy, as in one person killed members of the other person’s family, were finding reconciliation and forgiveness, demonstrating true affection for one another. Many of them had lived together as neighbors their whole lives before the killing. Now they were rebuilding the community that had been destroyed in 100 days of killing where a million people perished.

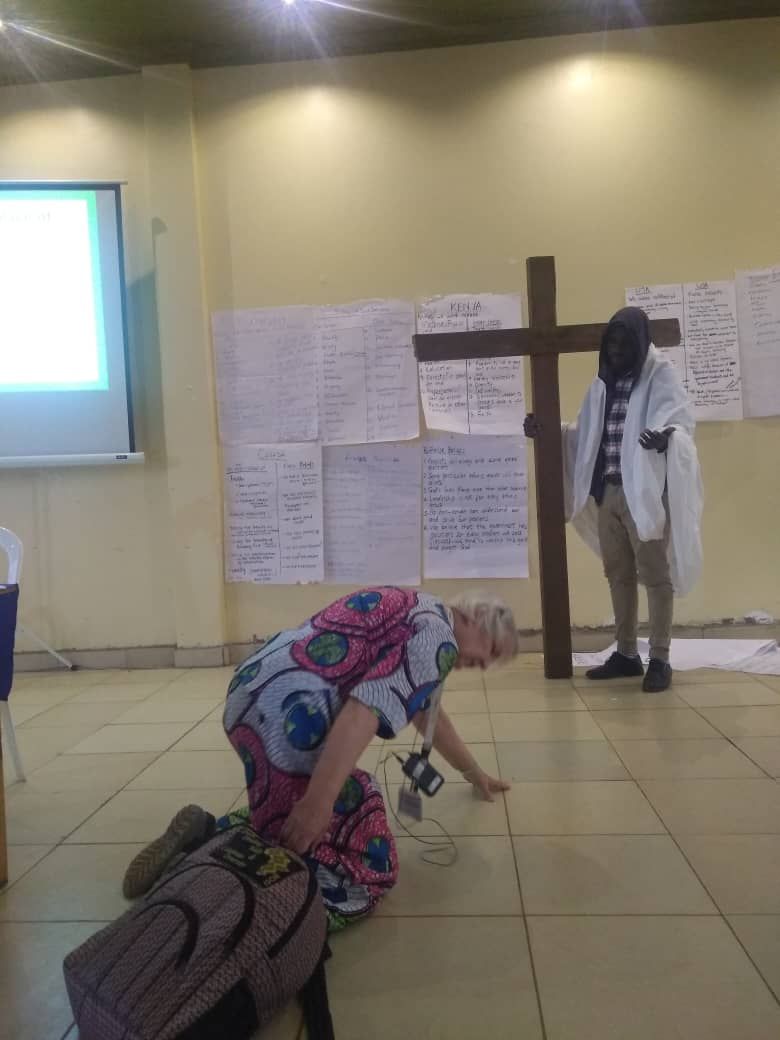

I am beginning my sabbatical by traveling again to Rwanda to go attend their International School of Reconciliation where I will learn the process they use to bring wholeness and fraternity where formerly there was only loss and pain. I want to understand how they harness the power of the Spirit to do what seems impossible. I have seen evidence of this transformation in people’s lives, but still it is a mystery to me how this can be fostered in human hearts. I want to learn it for myself, so that I might more readily forgive others. I will spend three weeks in the Rabagirana mission compound in Masaka, Rwanda, with a few Westerners and a number of Africans from 12 different countries. We will utilize a curriculum developed in response to the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. I began early in our sessions searching my heart. The question arose, “who do I need to forgive?”

William Bausch wrote that forgiveness is “putting up with an uneven score.” None of us like the way an uneven score feels.

Paul writes in Colossians 3:13 that if we have a claim against someone else, we should forgive them as the Lord has forgiven us. Paul is saying that God puts up with an uneven score when it comes to us, and we should do the same with those around us. I know, at least for me, this does not come naturally. Earlier in chapter 3 Paul writes about putting on “the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge in the image of its Creator [v. 10].” I want to learn how believers in Rwanda are putting on this new self and putting to death what belongs to our earthly nature (v. 5).

It is all a work of the Spirit. I am going to Rwanda to learn how, by the power of the Spirit, to live happily with an uneven score.

I want to learn to lead others in the way of reconciliation

I want to learn to lead others in the way of reconciliation

In our isolation, we felt disconnected from the rising Coronavirus panic sweeping the West. Through limited blips of wireless connection I read of Americans hoarding toilet paper; it seemed like something from a movie. I began to think about these differing reactions to the spreading pandemic. The Africans among us and the nations from which they came were all taking the Coronavirus seriously, but they were not panicked. They demonstrated no impulse to hoard. Their intuitive response was to talk of sharing.

I reflected upon this, and this is what I surmise. Africans know that daily life is precarious. In their bodies and their countries they show the visible scars of the risks of living. Life has taught them to trust in the Lord, “double double,” as they say. They take this pandemic seriously, but they are not fearfully frantic. Some Americans, on the other hand, are possessed by fear. We don’t do well with things we cannot manipulate to our will. We tend to believe that money can remove nearly all of the risk from our lives. In a sense this is true; wealth brings preventive health care, safer cars, lots of insurance coverage, and retirement accounts. The Coronavirus has disabused us of that illusion.

As Americans were busy stripping the stores of hand sanitizer and paper products, my fellow students and I were busy butchering two goats in Masaka. As we waited for the people in the kitchen to finish preparing the seasoning so we could get to barbecuing, we stood around the fire in the night. Soon we found ourselves dancing and singing. In other words, spontaneous joy broke out, Coronavirus notwithstanding. Trusting in God, even in times of challenge, is a license for joy. A dearth of spontaneous joy is the price we pay for believing that we can insulate ourselves from the vagaries of life through wealth and possessions. We find ourselves less prone to dance when we are not busy doing anything else. Relying on our own efforts to secure our lives robs us of trust in God, the source of all joy and peace of mind. Poverty is not to be praised; but wealth, on the other hand, cannot do for us what it promises.”

It is all a work of the Spirit.